MCB TRANSCRIPT

Brain Function: How Immune Cells Protect Neural Health and Memory

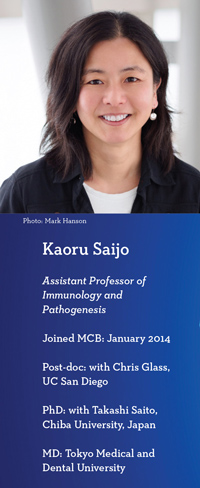

MCB Assistant Professor Kaoru Saijo uses neural diseases as a window to see how the brain works. “Understanding what isn’t working when patients get diseases will help us understand the flip side — normal function,” she says. Her work could also lead to better therapies for disorders from autism to Alzheimer’s disease.

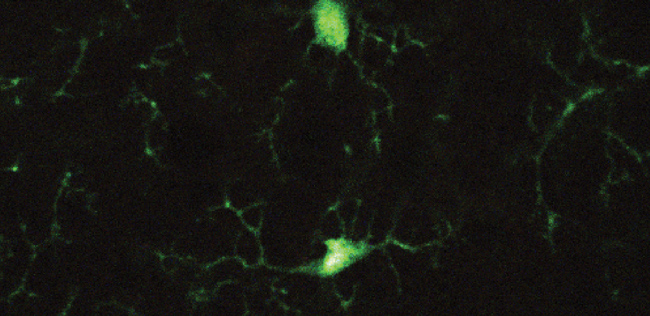

While most people who study neural diseases focus on neurons, Saijo focuses on microglia, immune cells unique to the central nervous system. “The brain is more than neurons,” she points out.

Like macrophages in the rest of the body, microglia in the brain eat pathogens. These brain immune cells also promote the inflammation that facilitates healing, and are implicated in neural diseases that involve chronic inflammation such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases. Interestingly, microglia also produce sex hormones — estrogens and androgens — that regulate genes both in microglia themselves and in other brain cells. “I’m totally fascinated with microglia,” Saijo says.

She first delved into the intersection of immunology and endocrinology in the brain as an MD-PhD student, when she investigated how hormones regulate the brain’s immune system. Her interest in microglia began as a post-doc, when she discovered that Nurr1 — a gene that is mutated in some people with familial Parkinson’s disease — inhibits hyperinflammation in microglia and so protects against Parkinson’s disease.

Today, Saijo wants to know if microglia are also linked to autism, which affects one in 68 children born in the U.S. and has no good drug therapies. Autism is associated with immune problems during pregnancy in women, and inducing inflammation in pregnant mice results in pups with autism-like symptoms. To see if microglia are implicated in autism, Saijo is testing whether gene mutations that cause autism also cause immune cell malfunction in developing mouse brains. She’s also testing whether microglial malfunction is caused by androgen and estrogen receptor mutations that are linked to autism.

Saijo also wants to know if microglia are linked to Alzheimer’s disease, which slowly erodes memories in the elderly. While microglia are key to memory, we don’t know what role they play in this process. “What’s wrong with old microglia?” she asks. “Maybe they are doing something bad to neurons so people can’t form memories any more.” Alzheimer’s disease is linked to lower estrogen levels, for example in postmenopausal women, and Saijo is testing whether this impairs microglia.

Studying neural disorders that arise when life begins and ends makes perfect sense to Saijo. “We believe that microglia are involved in brain function throughout life, and want to know how to restore normal function,” she says. “That is our dream.”

Saijo has been named a 2015 Searle Scholar along with 14 other talented young scientists from institutions all over the United States.