New Faculty Profile | Max Staller

A New Look into Old Problems

By Kirsten Mickelwait

“As a researcher, my philosophy has been to revisit old problems with quantitative approaches and more careful interrogations,” Max Staller says. His lab uses experiments, computation, and theory to study gene regulation, studying how transcription factors activate gene expression in yeast and human cells.

Staller joined the department in July as an assistant professor in residence in the Division of Genetics, Genomics, Evolution, and Development (GGED). He came from UC Berkeley’s Center for Computational Biology, where he’s still an affiliate. Previously, he received his PhD from Harvard and did his postdoc at Washington University in St. Louis.

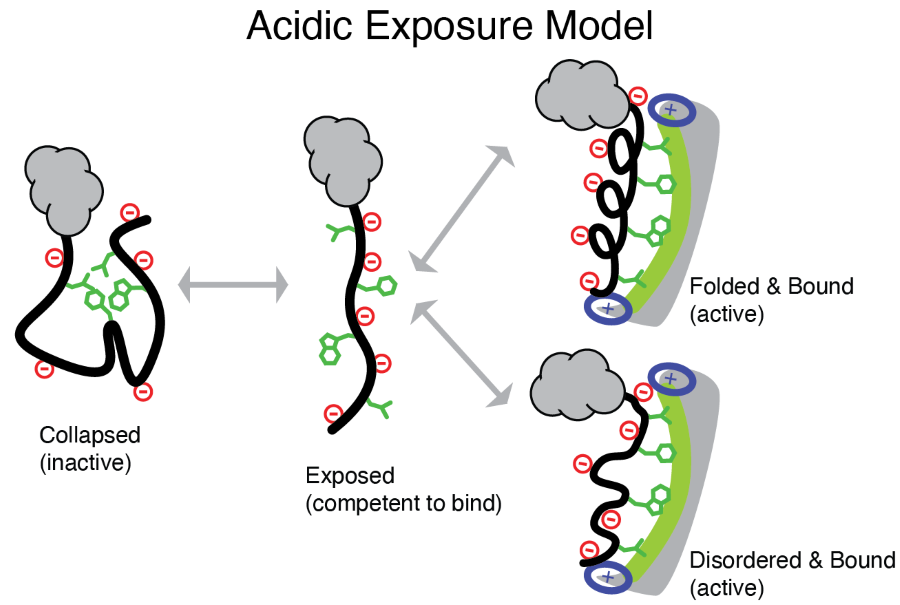

Staller’s primary research question asks: how do cells turn on genes? For example, we know that our liver cells are different from our brain cells because they've activated different gene expression programs. Most of this difference in gene regulation and expression is due to “transcriptional regulation.” The Staller Lab studies a piece of that process—how specialized regulatory proteins work.

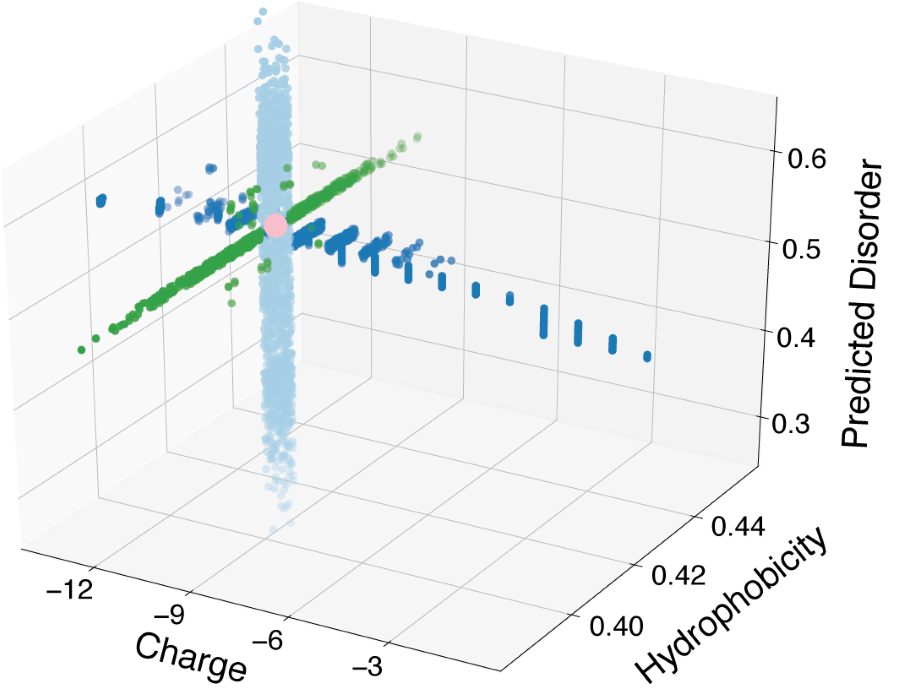

For the last 20 or 30 years, the field has been very focused on how these proteins bind DNA, Staller says. “I'm interested in how they work after they bind DNA, how they activate, and what their other jobs are. We use high-throughput methods and next-generation DNA sequencing to study regulatory protein function.”

The lab has begun a project, funded with a two-year grant funded by the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI), to study about 120 of the roughly 400 genes that have been causally associated with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). The work aims to build proof-of-concept computational models for classifying patient mutations in transcription factors. Long term, such models could be extended to other developmental disorders controlled by transcription factors such as pediatric and adult blindness—potentially even classifying subtypes of cancers.

The first translational frontier will be improved diagnoses, ultimately leading to the development of treatments. In the future, patients will be able to have their genomes sequenced and, if new mutations are evident, some descendant of Staller’s models will predict whether the mutation is benign or pathogenic.

It turns out that this is a very personal area of inquiry: Staller’s sister was born blind, nonverbal, and with an intellectual disability. Some years ago, Staller convinced his parents to consult a geneticist, who suggested exome sequencing to determine whether his sister’s condition might be genetic.

“They found a perfectly causal mutation, which neither of my parents have, in a gene that's known to affect the eye and the pituitary gland,” he says. It was a transcription factor—exactly the kind of regulatory protein Staller had been studying. “It was such an eerie coincidence, initially I didn't want to look into it. But now we've started a project to work on that very protein and its close cousin.” One day, his research might lead to a way to diagnose such conditions.

Though already working at Berkeley, he chose to come to MCB for its wide range of research interests and its “off-the-charts” development in microscopy and other technologies. He also loves how accessible and friendly the faculty are across disciplines.

But the biggest draw for Staller was to be able to teach and advise students more directly. “Mentoring is the most important part of my job as PI,” he says. “My mentoring philosophy is grounded in patience, listening, empathy, and feedback. I’m a big believer in group work and peer-to-peer learning.” Before coming to Berkeley in 2021, he mentored many students from traditionally underrepresented groups. Because he’s Hispanic, he says he personally benefited from programs that help such students; now he wants to pay that forward. His proudest professional achievement is the inaugural Outstanding Postdoc Mentor or Teacher Award he received in 2019 from the Postdoc Society at Washington University.

In his off-time, Staller loves hiking and skiing but, with a three-year-old daughter and a second child due in November, he finds his energies are now spent more domestically, cooking and co-parenting with his wife. Gone are the “work hard, play hard” days of graduate school and his postdoc, he laughs. Now, it’s about setting clear boundaries between his roles as a scientist, teacher, and dad.

And he’s excited that his work has led him to the MCB community. “I tell my friends that this is an intellectual paradise,” he says. “There are people working on basic mechanisms of biology, all sorts of interesting evolution—problems I’m really interested in.”

Learn more about research in the Staller Lab: stallerlab.com. It’s currently recruiting at both the student and postdoc levels.

Back to Main Fall 2023 Newsletter Page

| Connect With Us! | ||||

MCB X (formally Twitter) |

LinkedIn Postdocs, PhDs, or Undergrads |

Cal Alumni Network |

Give to MCB |

|